Well, it depends on a lot of factors.

Most people experience a bit of discomfort on a particular day, the way one feels before sickness overwhelms the body’s defences, and turns from a minor irritation to a full-fledged cold or fever, with watery eyes, soaring temperatures, shivering body and host of other unwanted symptoms.

Exercising while you’re sick, certainly won’t hurt your immune system, but, how sick you are; what is the intensity of the workout; what’s your general immunity, like do you feel sick often; and a lot of questions needs to be answered, and that’s why the decision to workout when sick, will depend on a case to case basis.

If you’re suffering from slight running nose, or a sore throat, then you may workout, but moderately. High intensity workout or heavy resistance training sessions should not form the part of your workout in any case, where you fear illness. May be going for a relaxing walk, or a cycling session, or even a light swim, would be fine on these days.

However, if you’re having worsening symptoms like heavy running nose, soaring body temperature, body pain, coughing, joint aches & pains etc. then you are better off exercising at all and relaxing yourself, in your cozy bed, may be with a cup of hot green tea/black coffee with ginger, cinnamon and turmeric, to give you the much-needed antioxidant boost.

The best bet here would be to sleep, as much as you can. Lying in the bed and working on your laptop or cellphone, won’t make things any better. Take complete rest, and it starts from more a deep sleep.

You would be probably fine, in a day or two, and resume your exercises, but do not start full on with high intensity sessions. Your body needs time to recover. Start slow, and progress gradually.

Most healthy people who have a minor cold, cough or mild bronchitis (without fever) can continue to exercise during their illness. However, you should aim at reducing your workout intensity and duration, by 50%. If you feel good the next day after your lighter workout, you can gradually increase your intensity. But if you feel exhausted and feel the symptoms worsen, take a day off.

With the flu or any respiratory illness that causes high fever, muscle aches, and fatigue, wait until the fever is gone before getting back to exercise. Your first workout should be light so you don’t get out of breath, and you want to progress slowly as you return to your normal routine. You may be tempted to ramp it up, but it’s best to go low (low intensity) and go slow (short duration).

Understand that, when your do intense training session, you do not get stronger there and then. Heavy training awakens a stress response in the body, and you eventually adapt to this stress by getting stronger. But when you’re sick, the intense workouts are putting too much load on the immune system, for it to handle.

However, even when you’re mildly sick, you don’t have to be completely sedentary. Active rest is always a better option. Going for light walks, a bit of yoga etc. will help you ward off the diseases much faster.

Athletes engaged in competitive sports need extreme practice sessions, multiple times a day. When you’re engaged in such high amount of physical workload, the body is vulnerable to various immune infections.

A study, suggested that unusually heavy acute or chronic exercise is associated with an increased risk of upper respiratory tract infections. The risk appears to be especially high during the one or 2-wk period following marathon-type race events. Among runners varying widely in training habits, the risk for upper respiratory tract infection is slightly elevated for the highest distance runners.

Acc. to the study, “Clinical data support the concept that heavy exertion increases the athlete’s risk of upper respiratory tract infections because of negative changes in immune function and elevation of the stress hormones, epinephrine, and cortisol. On the other hand, there is growing evidence that moderate amounts of exercise may decrease one’s risk of upper respiratory tract infections through favourable changes in immune function without the negative attending effects of the stress hormones.”

Another study found that, for several hours subsequent to heavy exertion, several components of both the innate and adaptive immune system exhibit suppressed function. However, the immune response to heavy exertion is transient. Though data suggest that, endurance athletes are at an increased risk for upper respiratory tract infection during periods of heavy training and the 1 – to 2-wk period after race events.

Diminished neutrophil function in athletes during periods of intense and heavy training. Following each bout of prolonged heavy endurance exercise, several components of the immune system appear to demonstrate suppressed function for several hours. This has led to the concept of the “open window,” described as the 3- to 12-hour time period after prolonged endurance exercise when host defence is decreased and the risk of URTI is elevated

The majority of athletes, however, who participate in endurance race events do not experience illness. Of greater public health importance is the consistent finding of a reduction in upper respiratory tract infection risk reported by fitness enthusiasts and athletes who engage in regular exercise training while avoiding overreaching/overtraining.

Acc. to a study, regular moderate exercise is associated with a reduced incidence of infection compared with a completely sedentary state. However, prolonged bouts of strenuous exercise cause a temporary depression of various aspects of immune function (e.g., neutrophil respiratory burst, lymphocyte proliferation, monocyte antigen presentation) that usually lasts app. 3-24h after exercise, depending on the intensity and duration of the exercise bout.

Post-exercise immune function dysfunction is most pronounced when the exercise is continuous, prolonged (>1.5hrs), of moderate to high intensity (55–75% maximum O2 uptake), and performed without food intake. Periods of intensified training (overreaching) lasting 1wk or more may result in longer lasting immune dysfunction.

Although elite athletes are not clinically immune deficient, it is possible that the combined effects of small changes in several immune parameters may compromise resistance to common minor illnesses, such as upper respiratory tract infection.

A study, evaluated potential preventive effects of meditation or exercise on incidence, duration, and severity of acute respiratory infection (ARI) illness, on over 150 adults, aged 50yrs or more. Researchers observed substantive reductions in ARI illness among those randomized to exercise training, and even greater benefits among those receiving mindfulness meditation training.

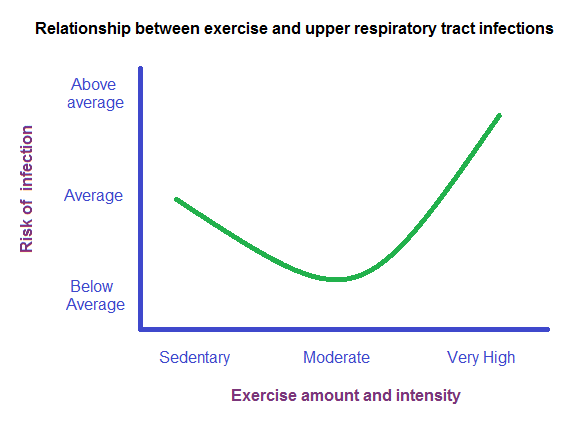

Most researchers have given the famous J-shaped curve, comparing immunity and exercise. This curve simply shows that being sedentary or overtraining, both can lower immunity.

Using a J-shaped model for exercise & infection, a study, examined differences in URTI risk between physically inactive and moderately active, 547 healthy men & women aged 20-70yr, and concluded that moderate levels of physical activity are associated with a reduced risk for URTI.

Also, your life and health are not just influenced by workout related stresses. Everyday there are many stressful events you face. Be it environmental (pollution, traffic jams etc.), psychological (family, office, relationships etc.), lifestyle (medicines, poor diet etc.). The more stress of different types your body faces every day, faster you are likely to get sick.

For e.g. you’re a long-distance runner, living in a polluted city, plagued with traffic jams. On top of that, you’re having family issues and work-related stresses. You are much more likely to fall sick than someone living in a cleaner environment with minor social issues.

An extensive study summarized the research on link between exercise & body’s defence system:

- Acute exercise (moderate-to-vigorous intensity, less than 60 min) is now viewed as an important immune system stimulant. Each exercise bout improves the antipathogen activity of tissue macrophages in parallel with an enhanced recirculation of immunoglobulins, anti-inflammatory cytokines, neutrophils, NK cells, cytotoxic T cells, and immature B cells. With near daily exercise, these acute changes operate through a summation effect to enhance immune defence activity and metabolic health.

- In contrast, high exercise training workloads, competition events, and the associated physiological, metabolic, and psychological stress are linked with transient immune perturbations, inflammation, oxidative stress, muscle damage, and increased illness risk.

- Illness risk may be increased when an athlete competes, goes through repeated cycles of unusually heavy exertion, and experiences other stressors to the immune system. 2%-18% of elite athletes experience illness episodes, with higher proportions for females and those engaging in endurance events. Other illness risk factors include high levels of depression or anxiety, participation in unusually intensive training periods with large fluctuations, international travel across several time zones, participation in competitive events especially during the winter, lack of sleep, and low diet energy intake.

- There is an inverse relationship between moderate exercise training and incidence of URTI (Upper Respiratory Tract Infections). Regular physical activity is associated with decreased mortality and incidence rates for influenza and pneumonia.

- Regular exercise training has an overall anti-inflammatory influence mediated through multiple pathways. Each exercise bout and the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect of exercise training have a summation effect over time in modulating tumorigenesis,atherosclerosis, and other disease processes.