Blood Pressure is the pressure of blood pushing against the walls of your arteries. Arteries carry blood from your heart to other parts of your body.

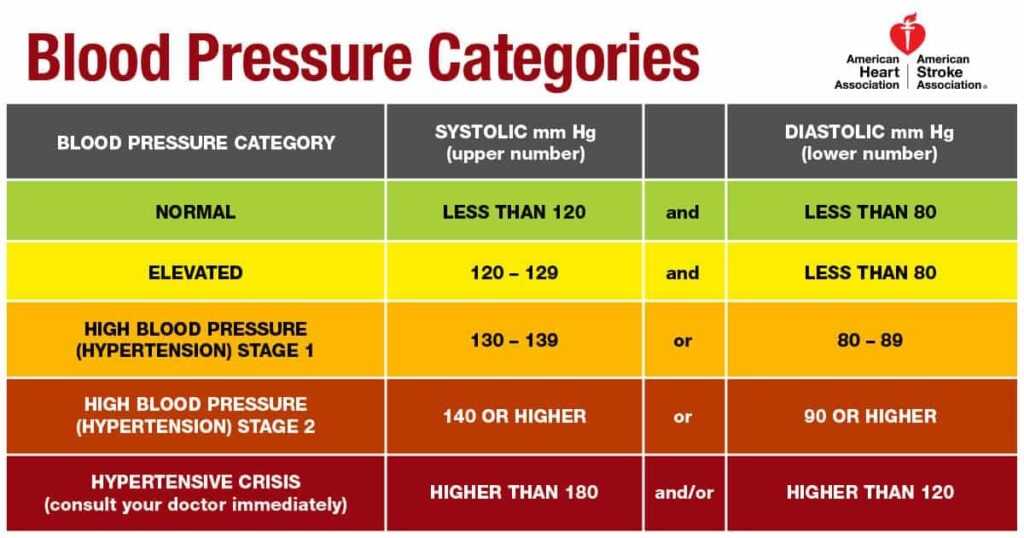

Blood pressure normally rises and falls throughout the day, but it can damage your heart and cause health problems if it stays high for a long time. Hypertension, also called high blood pressure, is blood pressure that is higher than normal.

In 2017, The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines released new guidelines, for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults.

Our focus would be to understand the link between physical fitness and hypertension. Acc. to the report:

- Studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship between physical activity and physical fitness and level of BP and hypertension.

- Even modest levels of physical activity have been associated with a decrease in the risk of incident hypertension. This means that, you do not have to “get in shape” to get the blood pressure benefits from exercise since blood pressure is lowered immediately following a single session of exercise for up to 24 hours. In other words, 30 minutes a day of exercise, might help keep the medicines away.

- Physical fitness, attenuates the rise of BP with age and prevents the development of hypertension.

- Higher physical fitness decreased the rate of rise in SBP over time and delayed the time to onset of hypertension.

- A BP-lowering effect of increased physical activity has been repeatedly demonstrated in clinical trials, especially during dynamic aerobic exercise, but also during dynamic resistance training and static isometric exercise (the strength exercises may be dynamic or isometric. Dynamic exercises are those in which you move your muscles and joints, such as a biceps curl or a squat. Isometric exercises are contractions of a specific muscle or group of muscles. During isometric exercises, the muscle doesn’t noticeably change length. The affected joint also doesn’t move).

The average reductions in SBP with aerobic exercise are approximately 2 to 4 mm Hg and 5 to 8 mm Hg in adult patients with normotension and hypertension, respectively. These BP reductions follow the “law of initial values” such that individuals with higher baseline BP values experience even greater reductions in BP from exercise training. In other words, exercise works best in those who can stand to benefit the most.

Increased physical activity has been an intrinsic component of longer-term weight reduction interventions used to reduce BP and prevent hypertension

BP-lowering effects have been reported with lower- and higher-intensity exercise and with continuous and interval exercise training. isometric exercise results in substantial lowering of BP.

The group of people with high to healthy blood pressure, also called stage 1 hypertension, is defined as people with a blood pressure reading of 130–139. For these people, dynamic resistance training is the first priority.

BP reductions of this magnitude lower overall CVD risk by 20-30%. For these reasons all major public health organizations universally recommend aerobic exercise for the primary prevention and treatment of hypertension. Similar to a drug prescription, individuals can be “prescribed” an exercise prescription for the prevention, treatment, and control of high BP following the FITT principle:

- Frequency: How often?

- Intensity: How hard?

- Time: How long?

- Type: What kind?

ACSM recommends the following exercise prescription for individuals with hypertension:

- Frequency: For aerobic exercise, 5-7 days/wk, supplemented by resistance exercise 2-3 days/wk and flexibility exercise ≥2-3 days/wk. Individuals with hypertension are encouraged to engage in greater frequencies of aerobic exercise than those with normal BP because we know that a single bout of aerobic exercise results in immediate reductions in BP of 5-7 mmHg, that persist for up to 24 hr.

- Intensity: moderate [i.e., 40-<60% VO2max or 11-14 on a scale of 6 (no exertion) to 20 (maximal exertion) level of physical exertion or an intensity that causes noticeable increases in heart rate and breathing] for aerobic exercise (like brisk walking); moderate to vigorous (60-80% 1RM) for resistance; and stretch to the point of feeling tightness or slight discomfort for flexibility.

New and emerging evidence suggest that the magnitude of the BP reductions that result from aerobic exercise occur as a direct function of intensity, such that the more vigorous the intensity, the greater the resultant BP reductions. Individuals who are willing and able may consider progressing to more vigorous intensities, however, the risk-to-benefit ratio has not yet been established., so one must progress slowly and carefully.

- Time: for aerobic exercise, a minimum of 30 min or up to 60 min/d for continuous or accumulated aerobic exercise. If intermittent, begin with a minimum of 10 min bouts.

New and emerging research has shown that short bouts of exercise (3-10 min) interspersed throughout the day may elicit BP reductions similar in magnitude to one continuous bout of exercise and may be a viable antihypertensive lifestyle strategy for individuals with limited time.

- Type: for aerobic exercise, emphasis should be placed on prolonged, rhythmic activities using large muscle groups such as walking, cycling, or swimming. Resistance training may supplement aerobic training and should consist of 2-4 sets of 8-12 repetitions for each of the major muscle groups.

For flexibility, hold each muscle 10-30 s for 2-4 repetitions per muscle group. Balance training (neuromotor) exercise training is also recommended in individuals at high risk for fall (i.e., older adults) and is likely to benefit younger adults as well.

A meta-analysis study showed that, dynamic resistance exercise training to result in BP reductions similar in magnitude to aerobic exercise training. However, one must be careful as inhaling and breath-holding while engaging in the actual lifting of a weight (i.e., Valsalva manoeuvre) can result in extremely high BP responses, dizziness, and even fainting and should be avoided during resistance training.

Another meta-analysis study, found that, resistance training alone reduces systolic and diastolic blood pressure in prehypertensive and hypertensive subjects, especially in elderly people.

The blood pressure response to resistance training depends on a number of factors including the amount of muscle mass recruited, breathing technique, amount of resistance lifted, number of repetitions, speed of lifting and rest between sets:

- The more muscle mass used during a resistance training exercise, the greater the blood pressure response. Performing exercises like leg press, leg extensions or chest press using both legs or arms together will increase blood pressure more than single leg/arm exercises.

2. The more weight lifted, the greater the blood pressure response. Avoid maximal or near maximal lifts.

3. The more repetitions performed, the greater the blood pressure response. Peak values are reached at the end of a set to exhaustion even with light loads. For this reason,hypertensives should avoid sets to failure. When effort becomes maximal at the end of a set, blood pressure will be highest.

4. The speed of lifting is also important. Blood pressure is lowest when lifting at controlled speeds but not too slow. Very slow lifting speeds result in greater blood pressure elevations.

5. Rest between sets also affects the blood pressure response. When rest between sets is 30-60 seconds, blood pressure tends to increase with successive sets. However, when rest was 90 seconds or greater, blood pressure was not significantly elevated during successive sets. Rest periods of 90 seconds or greater are recommended for hypertensives.

6. Another factor which plays a key role in minimizing the blood pressure response to exercise is breathing technique. Breath holding is not recommended as this can lead to the Valsalva manoeuvre.

7. If resting blood pressure is 180/110 mm Hg or higher, resistance training should not be performed. Hypertensive individuals with systolic blood pressures between 160–179 and diastolic blood pressures between 100-109 mm Hg should consult with their doctor before starting a resistance training program.

Precautions before starting exercise program in case of Hypertension:

- Appropriate health screening should be implemented to identify at-risk individuals who may require medical clearance before they begin an exercise program. Although exercise is safe for most individuals, there is a small risk of cardiovascular complications in certain susceptible individuals, particularly among sedentary adults with known or underlying CVD who perform vigorous-intensity exercise they do not usually engage in.

- Individuals with hypertension cleared to exercise (by the healthcare provider) should be encouraged to progress gradually, avoiding large increases in any of the components of the FITT.

- High-intensity resistance training should not be initiated for persons without prior exposure to more moderate resistance exercise independently of age, health status, or fitness level.

- Intensive isometric exercise such as heavy weight lifting can have a marked pressor effect and should be avoided.

- Progression should begin by increasing exercise duration over the first 4-6 week, followed by an increase in frequency and intensity to achieve the recommended volume of 150 min/wk or 700-2000 kcal/wk over the next 4-8 months. Progression may be individualized based on tolerance and preference in a conservative manner.

- If hypertension is poorly controlled, heavy physical exercise as well as maximal exercise testing should be discouraged or postponed until appropriate drug treatment has been instituted and blood pressure lowered. When exercising, it appears prudent to maintain systolic blood pressures at ≤220 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressures ≤105 mmHg.

- Antihypertensive medications such as calcium channel blockers, β-blockers and vasodilators may lead to sudden reductions in post-exercise blood pressure. Extend and monitor the cool-down period carefully in these situations.

- Patients should be informed about the nature of cardiac prodromal symptoms e.g. shortness of breath, dizziness, chest discomfort or palpitation and seek prompt medical care if such symptoms develop.